In this extract from A Race for Madmen, Chris Sidwells writes about the Tour de France's first foray into the Pyrenées in 1910

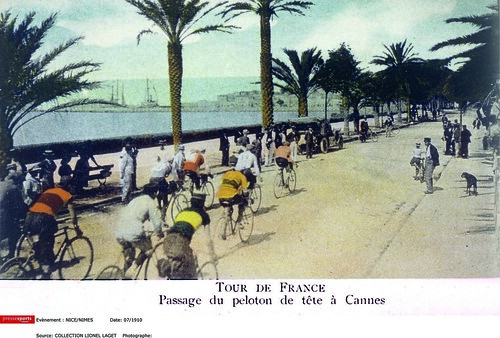

One of the first colour photos of the Tour, taken in Cannes during the 1910 race. Photo: Offside/L’Equipe

To ensure the riders’ safety and that no one would get left behind, Desgrange wrote [in L’Auto] that he was introducing to the Tour de France the ‘voiture balai’, the broom wagon, a truck that would be the last vehicle on the road and would sweep up any stragglers. It occupies the same position today, a token one, as the last Tour vehicle on the road. And there’s even a broom strapped to the back of it, but it’s been a long time since a Tour rider’s backside graced its seats. Modern Tour men who have to stop are whisked off to the finish in air-conditioned team vehicles or some other luxury transport to save them from the ignominy of the broom wagon.

All was set for the great day, but between May and July Desgrange began to worry. He worried even more when he heard there had been some recent bear attacks in the region, and by the time the Tour started it’s said that Desgrange was ill and confined to his bed.

Stage nine took the racers into the Pyrenées with some smaller climbs. Then came stage ten – the big one. Before it Steines briefed the riders. He told them not to take risks, and that the time limit that had been introduced, whereby a rider had to finish a stage within a percentage of the winner’s time, would be suspended.

The stage was 326 kilometres long between Luchon and Bayonne, and it had to start at 3.30 a.m. to ensure that there would only be a few tail-enders out on the mountains after dark. Battle raged between Octave Lapize and his team-mate, Gustave Garrigou, who won a 100-franc prize for climbing the Tourmalet without once getting off to walk. The two were well ahead at the top, which made what happened next look bizarre.

Alphonse Steines and a colleague, Victor Breyer, waited on top of the last climb, the Aubisque. They were expecting to see Lapize and Garrigou leading, instead an almost unknown rider, François Lafoucarde, wobbled into view. Breyer ran into the road and asked Lafoucarde what had happened – where were the others? He didn’t reply but just plodded past, staring straight ahead. Quarter of an hour later the next rider was more vocal. It was Lapize. Exhausted, half stumbling, half pushing his bike, he looked at Steines and Breyer and spat out the word ‘Assassins’.

He caught Lafoucarde, went straight past him, and won the stage. There were 150 kilometres still to ride from the top of the Aubisque, but from the way Lafoucarde dropped down the order, and the fact that he had been nowhere in contention on the Tourmalet, you can’t help feeling that he must have had assistance in a motor vehicle to leapfrog into the lead. Lapize rightfully took all the glory and the stage – while still complaining about the brutality of the route – and went on to dominate the rest of the race to win the 1910 Tour.

Everyone raved about how the magnificent men on their pedalling machines had tamed the wild mountains. France wanted more, so in 1911 the Tour gave them more. This time it was the Alps, the real Alps and the mighty Col de Galibier on a classic stage that included the Col d’Aravis and the stepping-stone to the Galibier, the Col de Telegraphe.

A Race For Madmen: The Extraordinary History of the Tour de France, by Chris Sidwells, is out now in paperback and Kindle in the UK; if you're in the US, see our book and Kindle links.

Read more from A Race for Madmen

The birth of the Tour de France

The first-ever Tour de France

The birth of the famous Yellow Jersey

The Tour de France goes into the mountains